The Australian government has recently committed to spending an additional $375.3 million — with funding to be matched by state and territory governments — over three years on improving housing outcomes and reducing the number of people sleeping rough.

On the face of it, increased government spending makes sense. Demand for emergency accommodation is at a historic high due to people on low incomes being unable to afford increasing rent prices, access limited public and community services and secure permanent work. There are 35,000 people waiting for public and community housing in Victoria alone.

Yet history tells us that we won’t end homelessness in Australia by building more crisis accommodation, and it’s clear we can’t rely on the private market to fill the growing housing gap. We’ve known since 1988 that social housing plays a crucial role in reducing homelessness, alongside government spending on community services like emergency shelters, mental health clinics, and criminal proceedings.

So what’s stopping us from investing in social housing and replicating the success we’ve seen in countries like Finland? The Nordic country is the only EU state not in the midst of a housing crisis and has just 52 shelter beds in the entire country, a reduction from 600 in 2008. Finland’s success has been attributed to a major government investment in social housing, which focused on moving people into permanent homes as soon as they became homeless instead of accessing crisis services and entering the system.

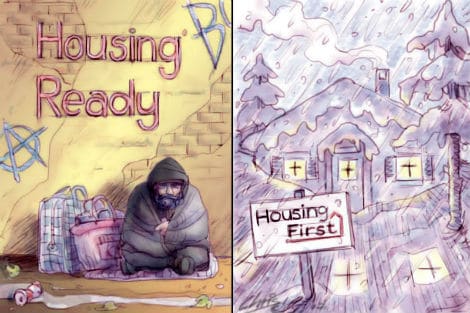

This Housing First approach does not require people experiencing homelessness to address all of their problems including behavioural health problems or to graduate through a series of services before they can access housing. The model assumes people have to be housed in order to get ‘well’, and that allowing the person experiencing homelessness to have a choice over their home and how they interact with community support services increases the likelihood they will remain in their house and improve their life.

In Australia, like most western countries, there has been a political shift away from the provision of public social housing and the Housing First model. This is because as a society we still see homelessness as an issue of personal pathology or deviance, not as a sign that our housing markets and community services are dysfunctional.

As a result, our approach to homelessness and, therefore, our services, are built around making people ‘ready’ for housing or helping them to address certain issues in order to gain access to permanent housing. This Housing Ready approach positions housing as a reward that those experiencing homelessness must prove themselves worthy of.

Recent research conducted in Ireland, however, shows us that traditional explanations around homelessness to do with mental health, addiction and institutionalisation aren’t the root cause of homelessness. The country has seen an extraordinary increase in homeless families over the last two years from nearly 100 families to about 1500 families in Dublin as a result of social housing no longer being built. Ireland historically has been dependant on the private sector which proved unstable during the economic crisis, causing housing prices to soar and forcing low-income families onto the streets.

While we may be oceans apart, there are valuable lessons to be learned from Ireland’s and Finland’s responses to homelessness. Contrary to popular belief, the Housing First model does work and is already being implemented in Australia. Common Ground is a Housing First initiative that has helped over 100 chronically-homeless people in the last five years find permanent, subsidised housing. Once housing was secured, the clients were then able to access wrap-around support systems for a range of services from substance abuse to cooking to budgeting so they didn’t fall back into homelessness.

By adopting the Housing First model, the Australian government could save millions over the next five, ten and 20 years as evident by countless research. One recent Australian study found that people used $13,100 less in government-funded services when securely housed — $35,117 down from $48,217 over a 12-month period. But it never was about the cost of homelessness services, was it? We know that it costs the government less to end chronic homelessness than it does to perpetuate the cycle of homelessness. Now it’s time for us to advocate where we want to invest our public money and to what end.

This piece was originally written for and is featured on Eureka Street.